Anti-Copyright in Artistic Subcultures

“From Lautréamont onwards…”

Coined in 1998 by university professor David Wiley in 1998, “Open Content” adapted Open Source licenses from the world of GNU, Linux and BSD software to publishing media. A few years later, with Wikipedia and Creative Commons, the concept had its break-through. The principle idea, however, of allowing works to be more freely used than under default copyright provisions, wasn’t new. In the 1930s, American folk singer Woodie Guthrie printed his songbooks with the following remark:1

This song is Copyrighted in U.S. under Seal of Copyright #154085, for a period of 28 years, and anybody caught singin it without our permission, will be mighty good friends of ourn, cause we don’t give a dern. Publish it. Write it. Sing it. Swing to it. Yodel it. We wrote it, that’s all we wanted to do.

Between 1958 and 1969, the Paris-based journal of the Situationist International, an artistic and politic avant-garde group, appeared with the following, more formal imprint:

“All texts published in Internationale Situationniste may be freely reproduced, translated or adapted, even without indication of origin.”2

By lifting restrictions on copying, performance, editing and even publishing of an edited work, Guthrie’s and the Situationist policies meet all criteria of a free or Open Source license given by the Free Software Foundation, in the Debian Free Software Guidelines and the Open Source Definition. But Guthrie is closer in spirit to contemporary Open Source and Free Software culture because he still maintains his copyright while permitting free use. Likewise, the “copyleft” of the GNU General Public License (GPL) is no anti-copyright. Its policy that derived works of a GNU-licensed work may only be published under the same GNU license tactically uses copyright in order to ensure a non-proprietary circulation of code. The notion of plagiarism and law-breaking copyright infringement also exists in GNU culture, for example, when copylefted code is used in non-free software, or when the copyright notice of a GNU program has been removed.3

There is thus a difference between a Guthrie-style, generous exercise of one’s copyright and an outright refusal of copyright and “intellectual property”. This contradiction is as easy to be overlooked as it is characteristic for artistic and activist subcultures, their internal misunderstandings and ill-forged alliances.

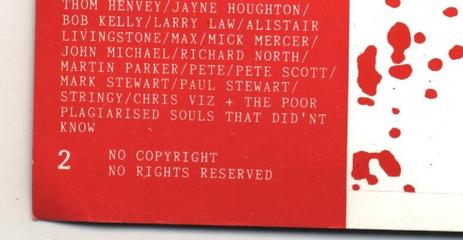

With articles on situationism, terrorism, William S. Burroughs and political conspiracies, the fanzine VAGUE played a seminal role in defining London’s radical chic of the late 1980s. Next to editor Tom Vague, a major force behind the paper was Jamie Reid, previously the graphic designer for the Sex Pistols and publisher of the situationist-influenced political underground magazine Suburban Press. With the slogan “No Copyrights. No Rights Reserved” and authorial credits to “the poor plagiarised souls that didn’t know”, VAGUE’s imprint radicalized situationist non-copyright into polemical anti-copyright. Under the headline “None dare call it plagiarism”, the editorial of issue 18/19 reasons that “From Lautréamont onwards it has become increasingly difficult to write. Not because people no longer have anything to say, but because Western society has fragmented to such a degree that it is now virtually impossible to write in the manner that has traditionally been considered ‘good’”.4 The text concludes: “In short, plagiarism saves time and effort, improves results and shows considerable initiative on the part of the individual plagiarist”.

While the text is signed with the name of editor Tom Vague, the passages quoted above were copied literally and without attribution from an issue of SMILE, an underground magazine published by multiple editors independently from each other. In turn, a later SMILE issue lifted the cover illustration of VAGUE #18/19, a photograph of two Molotov cocktails.

The name SMILE is a travesty of FILE, a paper published by the Canadian artist group General Idea that originally imitated the graphic design of LIFE magazine. FILE in turn had been parodied by Anna Banana’s mail art periodical VILE and Bradley Lastname’s fanzine BILE in the early 1980s. SMILE mutated, among others, into MILES, SLIME, LIMES, LISME, EMILS, C-NILE and iMmortal LIES. As an “international magazine of multiple origins”, it appeared in more than one hundred known issues published by different editors in Europe, America and Australia many of whom adopted the collective pseudonyms Karen Eliot and Monty Cantsin. Implicitly criticizing the “From Lautreámont onwards...” manifesto, a US-American SMILE issue from 1986 attacks “reactionaries” who “will always mistake this refusal to participate in the artificial separation between the ‘rational’ and ‘irrational’ for an inversion of the control structure of social relations”, “strengthen[ing] this misconception by attempting to show a historical line running from Lautréamont onwards, and by this linear method avoiding the central paradox of such criticisms.”5

Slightly abridged and attributed to Luther Blissett, the SMILE manifesto “From Lautréamont onwards” reappears in the book Mind Invaders in 1997.6 The very first version of the text was most likely written by SMILE’s initiator, Stewart Home, and inspired by at least three concepts and currents: The situationist method of “détournement”, itself an adaption of Lautréamont’s notion of plagiarism, 1980s American appropriation art of Sherry Levine and Richard Prince and Kathy Acker’s postmodern poetics of plagiarism in her own pop novels. Neither Home, nor other editors of SMILE and VAGUE were aware of the manifesto Imagination as Playgiarism written by American experimental novelist Raymond Federman in 1976, a point of reference for Acker. According to Federman,

[...]imagination does not invent the SOMETHING-NEW we too often attribute to it, but rather [...] (consciously or unconsciously) it merely imitates, copies, repeats, proliferates – plagiarizes in other words – what has always been there. For indeed, as it was once said: Plagiarism is the basis for all works of art, except, of course, the first one, which is unknown.7

Luther Blissett is another multiple-use identity, modeled after SMILE, Monty Cantsin and Karen Eliot. It was launched as a mass media phantom in 1994 in Italy; in 1999, the initiators declared his “seppuku”, ritual suicide. Still under the Blissett moniker, the group published “Q”, a historical novel that tells the history of Italian counterculture in the disguise of the reformation age. The book became an international bestseller while its imprint permits copying and redistribution for non-commercial purposes. Not only is this clause closer to Guthrie than to anti-copyright. Written in conventional narrative prose, the book disagrees – implicitly, but clearly enough – with the statement that writing had become more difficult after Lautréamont.

There yet more variants of the latter manifest. One of them is signed by the American Plunderphonics band Tape-beatles and attempts to shift the argument to music:

“From Stockhausen onwards it has become increasingly difficult to create new music. Not because people no longer have anything to say, but because Western society has fragmented to such a degree that it is now virtually impossible to write in the style of classical, coherent compositions.”8

The final sentence of the text, “plagiarism saves time and effort...”, can also be found in an Internet essay Plagiarism and Why You Should Use It9 signed Luther Blissett and published on the (nowadays defunct) web site of the phutile international, a movement that advocates “Phutilitarianism” as an “open source philosophy” and has links to the fanzine “Semtext”, a parody of “Semiotext(e)”.10

In the special issue Copy Culture of the art journal New Observations, edited in 1994 by Lloyd Dunn and other anti-copyright activists from the periphery of the Tapebeatles, it is claimed that “Homer was the first Karen Eliot”. Similar arguments can be found both in contemporary Open Source debates and in those published by Dunn in the late 1980s and early 1990s in his small press magazines Photostatic/Retrofuturism and YAWN.11 Their most annoying variants recur to categories of natural justice or even laws of and freedoms given by nature. The agrarian rhetoric of “the creative commons” has a questionable implication of culture as something organically grown rather than a social construct., based on natural right, and anti-copyright, based on rewriting culture, are in exactly these two opposite camps.

The following statement on anti-art, published in SMILE 8 in 1985, applies to anti-copyright as well: “Anti-art is art because it has entered into a dialectical dialogue with art, re-exposing contradictions that art has tried to conceal. To think that anti-art raises everything to the level of art is quite wrong. Anti-art exists only within the boundaries of art. Outside these boundaries it exists not as anti-art but as madness, bottle-racks and urinals”. Anti-copyright likewise exists only in its dialectics to copyright whose contradictions it exposes. Therefore, Homer is not the first Karen Eliot or Luther Blissett. Artists from other eras and cultures that don’t have strong notions and politics of intellectual ownership can’t be either.

Most conceptions of god-given “commons” don’t have more solid ground than wishful romantic thinking. The Situationist International – and its predecessor, the Lettrist International – and Open Source culture even have a common reference for their philosophies of sharing, Marcel Mauss’ anthropological study The Gift from 1924. Based among others on Bronislaw Malinowski’s field research, Mauss describes the “gift economy” of native American potlatch celebrations.12 “Potlatch” was adopted, among others, as the name of the bulletin of the Lettrist International, edited by Guy Debord. “Gift economy” was the key term used in 1998 both by the right-wing libertarian Open Source evangelist Eric S. Raymond and the socialist media scholar Richard Barbrook to describe the free exchange of software and information in the Internet13 – with Raymond making up crudest behaviorist, Darwinist and homebrew-anthropological theories.

Both the situationists and Barbrook, but also Raymond omit the fact that there is nothing romantic in Mauss’ gift economies. They simply are capitalism with a reversed business model, forcing their subjects to spend rather than to sell. Nevertheless, “gift culture” lent themselves to perfect utopian-exotic projection, with the dialectical implication that the culture of “intellectual property” was a purely Western and, to bring Homer back into game, fairly recent construction; in other words, a cultural and historical degeneration from which one had to go back to nature. Provisions against the free use and reuse of works, however, can be found in almost any time and at almost any place where the concept of artistic individuality existed. The notion of plagiarism was coined by the Latin poet Martial who accused a competitor of “plagium”, kidnapping of his verse.14 In the European middle ages, individual troubadours insisted on the exclusiveness not of the contents, but the verse forms of their poetry.

Not does Internet culture step into the mud with its popular agrarian metaphors of the “commons” and the “rhizome”. The well-known theories of literary intextuality and the death of the author, with their footprints in Federman, Acker and finally SMILE and VAGUE, historically date back to the Russian critic Michail Bakhtin and his perception in the late 1960s through the structuralists in the Parisian Tel Quel group, most notably Julia Kristeva. They thoroughly misread Bakhtin as a Russian formalist and his theory of literary “dialogism” as structuralist, a myth still alive today. In the late 1920s, Bakhtin had observed in Dostoevsky’s novels that their text masks itself by speaking the language of its characters. Later, he identified masks and parody as the distinctive quality of the novel per se. Taking Rabelais’ grotesque novels as an example, “novelism” thus has its root in popular comic culture and carnevalistic parody of official discourse and high art.

With this theory, Bakhtin was just no formalist or structuralist. In his advocation for folk culture, he did neither fully contradict cultural politics of the 1930s15, nor 19th century romanticist philology with its praise of folk songs, folk tales and popular epics. The concepts of “collective intelligence” and “wisdom of crowds” in contemporary Internet culture follow the same tradition. Wikipedia’s forced-upon editorial consensus and the prevailing mainstream aesthetics of open-licensed “user-generated content” reveal the dark flip side of the “commons” as a liberal variant of “popular instinct” ideologies – “gesundes Volksempfinden” in German.

Guthrie’s music at least spells it with an “f” instead of a “v”. But upon close inspection, humorist and parodist appropriation strategies can’t be well compared to anti-copyright. A few years after launching SMILE, Stewart Home conceded that, from a plagiarist standpoint, it would have been more consequent to name the magazine FILE, like General Idea’s.16 Keenly reflecting the difference between plagiarism and parody, Raymond Federman called his own poetics “playgiarism” with a “y”. A Bakhtinian literary counter-canon, with the novels of Rabelais, Cervantes and Jean Paul, would fit its bill, likewise the use and reuse of themes and motives in 17th century music or Caravaggio’s and Rubens’ workshop painting.

Plagiarism’s simulated novelty reciprocally corresponds to the simulated historicity of fakes. Most religions and gnostic schools of thought have been founded on backdated pseudoepigrapha,17 and names of prophets and evangelists collectively used over generations. Rather than Homer, Hermes Trismegistus and Christian Rosenkreutz could be called Monty Cantsin’s and Luther Blissett’s ancestors. And indeed, these connections have been made by the Cantsin- and Blissett-activists themselves, for example in the early SMILE issues of the English Neoist Pete Scott:

The concept of plagiarism, after all, is implicit in the concept of writing, and Thoth must therefore be regarded as the god of plagiarism, Lord of the plagiaristic process. It is for this reason that all future SMILE editions should be consecrated to his name.18

In the same issue, Scott rephrases the early 17th century history of the original Rosicrucian manifestos, Fama, Confessio and The Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz:

“The Neoists first made themselves known to the world in the early 1970s when a document was circulated throughout the United States. This manuscript, known as the Fama, declared to the world the existence of an international brotherhood known as the Neoist Conspiracy, whose purpose was to bring about a new age of enlightenment. [...] Later in the 1970s a second Neoist document appeared in the States and was widely circulated throughout Canada and Europe. Once again the anonymous authors urged the same response. The third and final document in this initial series was published in Quebec in 1980. It was known as The Chemical Wedding of Monty Cantsin”.

Scott anticipated the later attempt among others of the subcultural London Psychogeographical Association to reinterpret situationist psychogeography and other counter-cultural practices in terms of hermetic philosophy. In another text, he calls Monty Cantsin, along the lines of Trismegistus and Rosenkreutz, “something between an enigma and an institution”.19 But just as anti-copyright dialectically mirrors copyright, this describes only one side of Cantsin, Eliot and Blissett. As open-use identities, they also destroy enigma and institutions. In the end, they neither resolve in hermetic philosophy, nor in folk culture.

In other words: all attempts of dating back anti-copyright or identifying it with popular culture, fail upon closer scrutiny. As said in the phrase “From Lautréamont onwards”, no explicit poetics of plagiarism can be found before the late 19th century. Lautréamont’s Poésies phrase the anti-copyright recipe for VAGUE, SMILE and company:

“Plagiarism is necessary. It is implied in the idea of progress. It clasps the author’s sentence tight, uses his expressions, eliminates a false idea, replaces it with the right idea.”20

Throughout the 20th century, this quote has been perpetually and mutated again and again. First, the situationists appropriate Lautréamont’s “plagiarism” and rename it “détournement”. The Hegelian notion of progress in Lautréamont’s text, somewhat paradoxically linked to plagiarism, caters to the Situationist International and its self-perception as, one the hand, an avant-garde in a time where artistic and political avant-gardes have become historical while, on the other hand, still pursuing Marxist political utopias. Along these lines, the situationist “détournement” combines Lautréamont’s “plagiarism” with Brecht’s “Verfremdungseffekt” (“estrangement effect”). An early situationist text honors Brecht’s Berlin-based Theater am Schiffbauerdamm, nowadays Berliner Ensemble: “In the workers states only the experimentation carried out by Brecht in Berlin, insofar as it puts into question the classic spectacle notion, is close to the constructions that matter for us today”.21 Thirty years later, SMILE and its allies translated “détournement” back into “plagiarism”. Through the “ism” suffix in the English word, differing from “plagiat” in French and other European languages, the denotation of a method – plagiarizing – could be given the connotation of an artistic movement.

PLAGIARISM

Aside from its theory on Homer as Karen Eliot, the “Copy Culture” issue of New Observations contained a report of the Festival of Plagiarism Glasgow, 1989, the fifth and last of a series of events that had begun in London in 1988 and continued in San Francisco, Madison and Braunschweig. The form of small, self-organized festivals had been adapted from the earlier Neoist Apartment Festivals (APTs). The APTs, in turn, borrowed from the Fluxus festivals of the 1960s. The 11th issue of SMILE, published for the Glasgow festival, exemplifies these borrowings. The cover headline, “Demolish Serious Culture”, is plagiarized from a banner from Henry Flynt’s picketing of a Stockhausen concert in New York’s Lincoln Center. The SMILE issue even includes an interview with Flynt, a philosopher and anti-art theoretician originally associated to Fluxus. Five years later, in 1994, the London-based Neoist Alliance plagiarized Flynt’s complete intervention during a Stockhausen concert in Brighton.

A photograph above the headline appropriates the Drip Music of the Fluxus artist George Brecht, an early “Fluxus event” score. It shows Stewart Home in almost the same pose as George Maciunas performing the piece in 1962 on the first Fluxus festival in Wiesbaden. In a perfect match, plagiarized Fluxus performances had been scheduled for the sixth day of the Glasgow festival.

All these examples represent marginal plagiarism of art that was marginal itself. This contradicts the Festival of Plagiarism in their claims of challenging the contemporary art system as a whole and questioning the notion of art. For sure, Fluxus already had become part of the “serious culture” canon in the 1980s. Its plagiarism in Glasgow and, four years earlier, on the Fluxus day of the 9th Neoist Apartment Festival in Ponte Nossa however didn’t provoke any art establishment, but ended up rather as a historical homage.

A photograph included in the festival report of New Observations is very telling about the institutional conditions and choice of material at the Festivals of Plagiarism. It shows the interior of an alternative art space. In the foreground, there is a photocopy machine, the rest of the room is filled with photocopied pamphlets, self-made T-shirts and collage work on the walls. Not visible in this picture are other materials used at the festival, such as VHS video and audio cassettes. All media are analog. Nevertheless, most printed matters were already designed with desktop publishing software. Anti-copyright activists hadn’t realized the plagiarist potential of digital information processing yet in 1989, although BBS culture and a computer underground already existed. The single exception at the festival was a computer game programmed by Graham Harwood and shown in the exhibition. Otherwise, computers were merely used as an authoring tool for analog text, image and sound media. With its gallery space and its use of media, the festival clearly puts itself into a contemporary art context. At the same time, the media are emblematic for subculture and amateur art practices:

- the photocopier is the production device of fanzine culture

- collages and photocopies were the primary media of Mail Art. With its origins in Ray Johnson’s New York Correspondance School, Mail Art mainly served the role of networking amateur artists whose work was modeled after Dada and Fluxus.22

- audio cassettes were, in the 1980s, the medium of a subculture of self-produced and home-recorded underground music.

These media and their aesthetic shaped both the Festivals of Plagiarism and related anti-copyright publications. Lloyd Dunn’s small press magazine PhotoStatic/Retrofuturism became, within the confines of its distribution, an international debate and theory forum of the Plagiarism campaign. As obvious in its name, PhotoStatic’s origins were in Mail Art and photocopy art, too. Starting with issue 29 from 1988, it incorporated a supplement Retrofuturism. Edited by the Plunderphonics band Tape-beatles, it injected the plagiarism campaign into its parent magazine. Retrofuturism first occupied the lower quarter of every PhotoStatic page, later half, until it merged with PhotoStatic to a periodical which, next to VAGUE and SMILE substantially contributed to the renaissance of situationist theory in artistic subcultures since late 1980s.

Unlike its British cousins, which to a large extent were about their own radical chic and subcultural brand, PhotoStatic/Retrofuturism was more interested in gathering as many different and diverse voices in the plagiarism debate as possible. Editor Lloyd Dunn took advantage of the fact that self-published zines were a subcultural mass phenomenon in late 1980s and early 1990s North America. Before the popular breakthrough of the Internet, zine publishing amounted to a vital net culture. Around 1990, the meta zine Factsheet Five reviewed more than 1300 different zines in each of its own issues. As part of this net culture, SMILE, VAGUE, PhotoStatic/Retrofuturism and the Festivals of Plagiarism could inject their discourse into Mail Art and related subcultures like underground cassette music, tactically disturb and thus involve them.

Since its beginnings, the Mail Art network had an implicit humanist ethic of democratic, open participation art. Habermas’ discourse ethics provides a good blueprint for describing the ideal of egalitarian communication in Mail Art. That also goes for its flip side, seeking consensus and avoiding conflict. In 1991, the American anarchist Bob Black characterized Mail Art as an art system whose relation to the official system of contemporary art was equivalent to the Paralympics versus the Olympics. Mail Art, according to Black, is not truly egalitarian, but just uses different criteria of reward. Like cliques, Mail Art wouldn’t honor the quality, but the quantity of participation and base its covert internal star system on that criterion.

Studying Mail Art archives and anthologies, one indeed gets a quick grasp of how its bulk boils down to poor copies of Dada, Fluxus and concept art, copies whose poverty is, above all, not reflected or turned into an artistic strategy; in other words: naive experimental art. Disturbing its belief in creativity, the plagiarism campaign thus brought up a painful subject. But the Festivals of Plagiarism, SMILE, VAGUE, PhotoStatic/Retrofuturism and the campaign for an art strike between 1990 and 1993 almost completely failed to reach the institutional contemporary art system – although historical conditions had provided a good opportunity. In the late 1980s, the contemporary art market overheated and went through a crisis in the early 1990s. In some countries, like France, it never recovered. But the art strike campaign lacked the competence, language and networks for infiltrating the official art system.

Even the provocation of subcultural credos of communication and creativity lost its edge fast. The plagiarism campaigns were requiring an aesthetic, communication platforms and participants. For lack of alternatives, they were all taken from Mail Art. Mail artists stood by as contributors because they were used to more or less arbitrarily providing subcultural exhibitions, festivals and publication with their rubber stamp and xerox artwork. It quickly took over the Festivals of Plagiarism. A good example are two print publications by the American artist duo Xexoxial Endarchy (Liz Was and Miekal And) made in 1988 for the first Festival of Plagiarism in London: a fake Lewis Carroll book and a fake Maya codex passed off as the oldest manifesto of artistic plagiarism. While both works sound interesting, they were executed with little artistic effort, as quick collages of blown-up text and image fragments. The photocopied covers, with their amateur typography, leave no doubt that this is typical Mail Art and not a believable fake. This is all the more ironic given that the aesthetic and technological constraints of xerox copying could have been perfectly used for forging a samizdat copy of a supposedly lost or shut-away manuscript ; needless to mention how that would have been an incomparably more radical reflection of artistic authorship, intellectual property and institutional authority.

The Mail Art aesthetics of the Festivals of Plagiarism was soon criticized from within the anti-copyright movement, most fiercely in two pamphlets anonymously published in Baltimore. In the leaflet History Begins Where Life Ends, a rebuttal to Stewart Home’s 1993 talk Assessing the Art Strike at the ICA London, the Neoist tENTATIVELY, a cONVENIENCE writes:

“No matter that the Festivals of Plagiarism were mainly art shows for collages & copy art & paintings & other such banal pictorial forms. No matter that Festivals of Recycling might have been more accurate descriptions. The important thing is that by virtue of calling the act of reusing & changing previously existing material (not even always with the intention of critiqueing said material) ‘Plagiarism’, the appearance of being ‘radical’ could be given to people whose work was otherwise straight out of art school teachings. If the process of reusing had been called something so uncontroversial as ‘recycling’ the festivals would have seemed more like the product of ‘outmoded hippie liberals’ & wouldn’t have sold nearly as well.”23

The second pamphlet, written by the Neoist, experimental musician and subcultural activist John Berndt, appeared in a SMILE issue where it was put next to a photographic reenactment of the cover picture of the Glasgow SMILE issue. The plagiarism of the plagiarism of George Brecht’s “Drip Music”, its caption falsely claims that Brecht himself (and not Berndt) was to be seen on it. Having participated in the London Festival of Plagiarism organized by Stewart Home and Graham Harwood in 1988, Berndt found that

“a repetitive critique of ‘ownership’ and ‘originality’ in culture was juxtaposed with collective events, in which a majority of participants did not explicitly agree with the polemics. Many of the participants simply wanted to have their ‘aesthetic’ and vaguely political artwork exposed, and found the festival a receptive vehicle for doing so. Throughout much of these ideas loomed ‘abstract’ questions of power, even at the level of event organization. In a very obvious way, ‘activists’ were structuring events and language to give weight to a programmatic agenda of ideas. At the same time, there was considerable dissent as to what those ideas consisted of.”24

Berndt concludes with a call upon for a Festival of Censorship, arguing that freedom of plagiarizing can only exist if monopolies of censorship have been abolished. Censorship, he writes, is more populist than plagiarism because it doesn’t require previous knowledge of sources. The duality of plagiarism and censorship can indeed be backed up with linguistics and semiotics: Every plagiarist selection and duplication of a sign implies a decision against selecting a different sign. Naive Mail Art, the recycling of the Festivals of Plagiarism and, one decade later, debates on free Internet culture systematically suppressed this negativity. They exemplify how anti-censorship rhetoric is censored in itself, as if to prove Lautréamont’s original statement about plagiarism which “eliminates a false idea” and “replaces it with the right idea” with its dialectic of multiplication and repression.

CRITIQUE OF Plagiarism

Pretending to disrupt the contemporary art system while a lack of competence and rigor kept them stuck in subcultural marginality, the anti-copyright and Art Strike campaigns of the Festivals of Plagiarism collapsed quickly. For a real provocation and disruption, they would have had to plagiarize established contemporary art and its social orchestrations rather than their own ghetto aesthetic. On top of that, American appropriation art had already played that game in the early 1980s. While it never aimed for more than success within the art system, it shows that plagiarism can only work in the same discourse, on the same level as the plagiarized objects. A plagiarized Warhol-Brillo Box will cease to be a plagiarized Warhol-Brillo Box once it is put into an apartment or supermarket. At a counter-cultural Festival of plagiarism, a counterfeit Duchamp Readymade boils down to an homage or just “bottle-racks and urinals”. With their physical and cultural locations alone, the Festivals of Plagiarism failed their own standard of breaking through subcultural self-assurance. Above all, they lacked the rigor and aplomb of admitting it. Instead, spurious arguments were brought up against more established artistic and academic competitors. To this end, the invitation text to the Glasgow Festival of Plagiarism resorted to blatant vitalism:

“[...] the , appropriations‘ of postmodern ideologists are individualistic and alienated. Plagiarism is for life, post-modernism is fixated on death.”

Even as purely conceptual art, the plagiarism discourse had its shortcomings. Its theoretical horizon remained limited to the 20th century art avant-gardes including the Situationist International. More radical concepts of appropriation can be found, for example, in the short stories of Jorge Luis Borges which the plagiarist subcultures hadn’t been aware of. In retrospect, it also seems as if the anti-copyright activists of the late 1980s were tilting at windmills, now that the art system copes with massive loss of relevance outside the narrow circles of curators and collectors. Both the plagiarism and the Art Strike campaign credited the art system with a canonical power that it had already lost back then. In the 1990s, the Luther Blissett project derived much of its success from giving up fixations on art and installing plagiarism, prank and anti-copyright tactics on a broader cultural basis.

With the Pirate Bay and the Pirate Party, this activism has now arrived in Hollywood. It challenges the culture industries more radically than Neoists and art strike activists would ever have dared to dream. At the same time, anti-copyright became a victim of its own success. From Lautréamont and the Neoist Apartment Festivals via recycling-infested Festivals of Plagiarism to the bestseller prose of “Q” and Bittorrent downloads, aesthetics have been become gradually less radical, and activists have deferred contestation of not just the culture industry, but culture as a whole.

Notes

- 1

- Quoted from Dmytri Kleiner, The Creative Anti-Commons and the Poverty of Networks, http://info.interactivist.net/article.pl?sid=06/09/16/2053224

- 2

- “Tous les textes publiés dans ‘INTERNATIONALE SITUATIONNISTE’ peuvent être librement reproduits, traduits ou adaptés même sans indication d’origine”, [Int69], p. 148

- 3

- Harald Welte’s initiative http://www.gpl- violations.org is about tracking such cases and bringing them to court.

- 4

- VAGUE #18/19, Control Data Manual, London, 1986

- 5

- SMILE 6/7, Baltimore 1986

- 6

- “From Lautréamont onwards it has become increasingly difficult to write, not because we lack ideas and experiences to articulate – but due to Western society becoming so fragmented that it is no longer possible to piece together what was traditionally considered ‘good’ prose.”, [Hom97], p. 133

- 7

- [Fed76], p. 565-6

- 8

- http://downlode.org/Etext/plagiarism.html

- 9

-

http://www.vgpolitics.f9.co.uk/00505.htm

- 10

- Former URL: http://www.phutyleinternational.com/acright/acright.htm

- 11

-

Thanks to Lloyd Dunn’s heroic work, all PhotoStatic/Retrofuturism and YAWN numbers can be freely downloaded in meticulously reconstructed PDF files from http://psrf.detritus.net.

- 12

- [Mau90]

- 13

- Richard Barbrook, The Hi-Tech Gift Economy, http://firstmonday.org/issues/issue3_12/barbrook/, Eric S. Raymond, Homesteading the Noosphere, http://www.firstmonday.org/issues/issue3_10/raymond/

- 14

Martial I, 52- 15

- I am plagiarizing unpublished critical thoughts of the literary scholar Martin von Koppenfels

- 16

- “Incidentally, I called SMILE that name for a number of reasons, one being a play with/on General Idea’s FILE. When I picked the name, I was not aware of VILE or BILE. If I had been more rigorous in thinking, I would have named it FILE, but it’s too late now”, in: Monty Cantsin (editor), Neoism Now, Berlin: Artcore Editions, 1986

- 17

- Which, of course, includes the Torah and the Bible.

- 18

- SMILE 23, Doncaster 1986

- 19

- Also cited by Paul Mann, Stupid Undergrounds in: Postmodern Culture, issue 5, 1995, http://www.iath.virginia.edu/pmc/text- only/issue.595/mann.595

- 20

- Improved English translation from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comte_de_Lautreamont

- 21

- Guy Debord, Report on the Construction of Situations and on the International Situationist Tendency’s Conditions of Organization and Action, 1957, http://www.bopsecrets.org/SI/report.htm

- 22

- [CS84]

- 23

- http://www.thing.de/projekte/7:9%23/tent_history_begins.html

- 24

-

Proletarian Posturing and the Strike that Never Ends, in: SMILE, Baltimore, 1989

REFERENCES

- [CS84]

- Michael Crane and Mary Stofflet, editors. Correspondence Art. Art Metropole, Toronto, 1984. 8

- [Fed76]

- Raymond Federman. Imagination as Playgiarism. an Unfinished Paper. New Literary History, 1976. 3

- [Hom97]

- Stewart Home, editor. Mind Invaders. Serpent’s Tail, London, 1997. 3

- [Int69]

- Internationale Situationniste, editor. Internationale situationniste. Édition augmentée. Librairie Arthème Fayard, Paris, 1997 (1958-1969). 1

- [Mau90]

- Marcel Mauss. Die Gabe. Suhrkamp, 1990. 4